Galgano

100+ Posts

We are in Hampshire for the last 10 days of a 7 week holiday, that took in Austria/Germany (Christmas Markets River Cruise), a week in London, 10 days in Cornwall (Mousehole) and a week in Devon (Dartmouth).

I'll post reports on each of these locations, however this report could be quite short as we aren't getting out and about as much as we did for the previous 6 weeks.

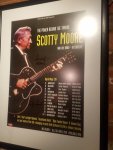

One of our sons teaches music composition at Southampton University and we are staying with he and his partner until his 45th birthday and a concert performance of one of his works at the end of January. Then back home to Sydney hoping the high 30c temperatures are a thing of the past back there.

Drew says I sometimes “over think” things. Such as? Why were the water pools and ponds in The New Forest so intensely blue today?

It was cold today. Actually, it was freezing. As I posted on Facebook today:

“In Australia, we more often refer to temperatures as being in their low teens or high teens in winter. That's Centigrade degrees. Here in the UK, the gauge in Drew's car measures it in half degrees. Half a degree is import when it's still only 3c at 11.00 am and finally registers 3.5c shortly after. Then the internet advise that it may be 3.5c but feels like -1c.

When I see ice on the footpath at 3.30 pm, all I know is, IT"S FREEZING!

Despite the above, the sun was out .... not shining, but out. We enjoyed The New Forest today.”

As usual, I digress. The water was intensely blue. Apparently when light shines into water, the water molecules absorb certain colours depending on the depth of the water and the base (sandy or rocky). The colours not absorbed, mix to create the colour we see. OK, I’m over thinking. The water was intensively blue and probably accentuated by the green of the fields. Then again, not having seen the sun and a blue sky in 6 weeks probably might have something to do with it.

We decided to visit parts of The New Forest we missed in 2017. Rockbourne is actually just outside The New Forest in the far north west. It’s so close to Breamore (Bremmer), also on our list, that we decided to go there first and work our way back.

The New Forest isn’t all forest. Approx. a third is heath and grass, with a third of that, wet grassland. That’s where we drove slowly across The New Forest. Lots of wet grassland and horses and ponies. To repeat what I wrote last time, the land is largely unfenced and “common” land. The stock are owned but all just intermix and roam free.

Most of the horses weren’t feeding (the Donkeys were). They all appeared to be just standing beside any available shrub, eyes closed and soaking up the rays of the sun. On several occasions when they were standing in the road, they made no effort to move as we slowly drove around them.

It only took 30 minutes to drive from Southampton to Rockbourne. Even at 60kmph and through several small villages and some narrow country lanes. All easier to see when you are driving that much slower.

Rockbourne is one long street. Probably 600m. On the south side, many of the houses/cottages abut the road. On the north side, the road is flanked by a brook (that’s a stream or creek in Australia). Why call a brook a brook, when you can call it “Sweatfords Water”. Every house/cottage on that side is reached by its own little bridge. All of the houses on both side are either Tudor or Georgian and the majority thatched. It was a case of driving through the town exclaiming “OMG” from beginning to end. The end being the only parking available in the village. The “Rose and Thistle” pub was the only public parking available, so we parked there and doing the right thing, entered for a coffee/tea.

The manager was in the process of lighting the two fires. Real timber fires … there isn’t any shortage of plantation and fallen trees in TNF. Most places now have artificial coal fires (gas) and it was great to smell real timber burning. Wonderful atmosphere with hunting paraphernalia and turn of the century (19th) Vanity Fair paintings of cricketers and hunters, decorating the walls and ceiling of this old Tudor Inn.

Warmed a little, we worked our way down the village. With the sun in our eyes, I photographed every dwelling on the north side on the way down and both sides on the way back. For ¾ hour, we strolled. Said hello to two guys re-thatching a large cottage and dodged a constant stream of cars. Like Pitt/Burke Sts.

As we approached the “Rose and Thistle” on our return, Ches decided to visit the ladies inside, while I went around to the carpark … it was full. Ches returned to say that the hotel was packed. Bar and restaurant. So the cars we had dodged weren’t travelling through, but too. That explained a reserved sign on a table we had seen in the bar. On a Wednesday? No idea.

The other feature of Rockbourne is a Roman Villa. It is quite extensive, and largely consists of some mosaics, the foundations of 70 rooms, and one large rectangular foundation of the bathhouse, with the hypocaust exposed. It was closed for the winter and the hedge around it impenetrable. I only know what it looks like because I googled.

I should have googled before we went to Rockburne. All we had was our 1974 AA Touring Guide of GB which mentioned Tudor and Georgian cottages. For anyone reading this, who decides to also visit Rockbourne, here’s what we missed:

Thanks Wiki

Overview

Rockbourne is a village of thatched, brick and timber houses, next to a stream now known as Sweatfords Water. The village consists chiefly of one street almost half a mile long. The church is in the northeast of the main street. Close to the church, adjoining the north side of the churchyard, is a manorial complex consisting of small L-shaped 14th-century house, now used as part of a modern farmhouse; the remains of a large Elizabethan or Jacobean house a short distance to the east; a 13th-century chapel near its southeast angle; and a large 15th-century barn running northward from the chapel.

History

Rockbourne has a long history of human habitation. Three Neolithic long barrows are known within the parish boundaries, as well as the sites of over twenty Bronze Age bowl barrows. At Knoll Camp, there is also the site of an Iron Age Hill fort with a single bank and ditch. At West Park, Rockbourne Roman Villa has been excavated since the 1950s, revealing over 70 rooms, several with mosaic floors and hypocausts. The collection of finds from the site have been housed permanently in the museum building on the site, which is the only villa site in Hampshire open to the public.

The name Rockbourne, recorded as Rocheborne in 1086, may derive from Old English "Hrocaburna", Rooks' stream, or perhaps Rocky stream. In the earliest records Rockbourne was a royal manor. In the Domesday Book of 1086, Alwy son of Turber held a hide there which Wulfgeat had previously held of King Edward.[9] Saewin also held half a hide of the gift of King Edward, to which the sheriff in 1086 made an unsuccessful claim as part of the king's farm, but which at a later date reverted to the Crown.

Alwy was succeeded here as in Hale and Tytherley by the Cardenvilles, and in the 13th century William Cardenville held a free tenement in Rockbourne.[4] Before 1156 the manor had been granted to Baron Manser Bisset. He was succeeded before 1177 by a son Henry, and whose widow Iseuld was holding Rockbourne early in the next century. Their eldest son William died c. 1220, and was succeeded by his brother John, who died in 1241. Rockbourne passed to his daughter Ela, and then to her son John who assumed his mother's surname. He died in 1307, leaving a son John, who died unmarried in 1334, leaving the manor to his sister Margaret, at that time the wife of Robert Martin, on whom the manor was settled in 1338.[4]

Early in 1336 Robert Martin complained that a certain John de Crucheston (Crux Easton) and others had abducted Margaret his wife and taken away his goods. Not waiting for justice, he retaliated by breaking into the house of John de Crucheston and seizing his property. Some years later he took Crucheston prisoner, torturing him "with cords tied round his head and other torments, and extorting £1,150 from his friends for his release." Robert Martin died in 1355, his wife surviving him until 1373, when the manor passed to her eldest son by her first husband, Sir Walter de Romsey. It then passed by inheritance into the Keilway family, it being held by John Keilway on his death in 1547. His son Francis died in 1601–2, and his son Thomas succeeded to Rockbourne, which, already heavily mortgaged to Sir Anthony Ashley, he sold in 1608 to Sir Anthony's son-in-law, Sir John Cooper. Sir John Cooper was succeeded by his eldest son Anthony Ashley Cooper, created Earl of Shaftesbury in 1672, and the manor descended with the Earls of Shaftesbury.

The nearby manor of Rockstead, which Aldwin held before 1066, belonged to Hugh de Port in 1086. Rockstead had passed to Breamore Priory before 1291. It belonged to the priory at the Dissolution and was granted with its other possessions to Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter and Gertrude his wife in November 1536. Escheating to the Crown in 1539, it was granted to Anne of Cleves, but in 1548 passed to Sir Thomas Henneage and William Lord Willoughby, who in the following year sold it to William Keilway. After this date it followed the descent of Rockbourne and became merged in that manor, its name only surviving in Rockstead Farm.

On to Breamore pronounced “Bremmer”. Again according to our AA Guide, “pure Tudor’. Triangular in shape with the large houses along the base and a green with small cottages at the apex and a narrow street through to the main road.

Let’s get things straight. Yes, several lovely thatched houses along the base. A “green” that resembles more “wet grassland” than a green on which you might play cricket or have a picnic. It turns out it is “the Marsh (an important surviving manorial green)”

Again, while I quite liked what we saw and photographed, it might help if more info was available and a map wouldn’t go astray as some of the sites aren’t as close to the village as suggested.

The Saxon church and Breamore House are about three-quarters of a mile west of the road and we had no chance of finding them and we only stumbled on the River Avon because Tom (our satnav) took us over oit on our way across country to our final destination Minstead.

Before leaving Breamore however:

“History

Breamore Down has several Bronze Age bowl barrows. There is also a long barrow known as the Giant's Grave, originally 65m long and 26m wide with flanked ditches, it is now partly damaged. Breamore Down also has a mysterious mizmaze on its heights. Argument rages as to whether the Bronze Age people or mediaeval monks were responsible for these patterns cut in the turf.

The name Breamore, recorded as Brumore in 1086, may be derived from Old English "Brommor" meaning "broom(covered) marsh". At an early date the manor of Breamore belonged to the Crown, and in 1086 was part of the royal manor of Rockbourne. At an early date, probably by grant of Henry I, Breamore passed to the Earls of Devon, lords of the Isle of Wight, who held it from the king in chief. In 1299, Edward I assigned it to his consort, Margaret of France, but in 1302 Breamore was delivered to Hugh de Courtenay. From that time it descended with the Earls of Devon until it was granted, in 1467, to Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy. In 1475, Breamore escheated to the king, who granted it for life in 1490 to Sir Hugh Conway and Elizabeth his wife. In 1512, it was granted to Catherine of Yorkwidow of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon and her heirs. Her son Henry was created Marquess of Exeter in 1525, but was beheaded in 1538–9, when the manor again passed to the Crown.

The manor was granted in 1541 to the queen consort, Catherine Howard, and in 1544 to Catherine Parr, who, after the death of Henry VIII, married Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, to whom Breamore was granted by Edward VI in 1547. On his execution in 1549 it again passed to the Crown and was granted in 1579 by Elizabeth I to Christopher Hatton. William Dodington purchased from him and died in 1600 leaving a son and heir Sir William. From this date Breamore followed the descent of South Charford until 1741, when Francis Lord Brooke sold it to Samuel Dixon, preliminary to its sale to Sir Edward Hulse.

Breamore railway station opened in 1866. It was served by the Salisbury and Dorset Junction Railway, a line running north–south along the River Avon, connecting Salisbury to the North and Poole to the South. It closed in 1964, the disused station still exists on the road that leads east from the A338.

St Mary's church

The church of Saint Mary is an almost complete example of an Anglo-Saxon church. The building consists of a chancel and aisleless nave separated by square central tower. The east window with net like tracery dates from 1340. There is a "leper window" in the north wall. Seven "double-splayed" Saxon windows remain. The chancel arch and arch in west wall of the tower are 15th century. The tower houses four bells cast in late 16th and early 17th centuries. There is an Anglo Saxon inscription dating from reign of Ethelred II, and a badly mutilated Saxon rood with figures of Our Lady and Saint John.

Breamore Priory

Main article: Breamore Priory

The priory of Breamore was founded towards the end of the reign of Henry I by Baldwin de Redvers and Hugh his uncle, to whose descendants the advowson belonged. It was apparently visited by Richard II in 1384. Baldwin and Hugh de Redvers endowed their priory of Breamore with certain land in Breamore which formed the nucleus of the manor later known as Breamore Bulborn. Various donors added gifts of adjoining land which were merged in the manor.

On the dissolution of the priory in July 1536 the site was granted in November of that year with the manors of Breamore and Bulborn to Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter and his wife Gertrude. It then followed the descent of Breamore Bulborn, becoming merged in that manor.

Breamore House

Main article: Breamore House

Breamore House stands north-west of the church. The original house was a very fine late 16th-century building of brick and stone, but was unfortunately burnt in 1856. It was restored on the old lines, incorporating such of the old masonry as was left, and now from a short distance still resembles an Elizabethan building.[8]

Breamore stocks

The village stocks can be viewed by the A338 roadside. They were originally at the road junction, but are now opposite the Bat and Ball Hotel. They were restored after being badly damaged by a lorry. The stocks have a whipping post and horizontals with four leg holes. A modern roof has been erected over them.”

It’s not easy to stop near the old mill and bridge that span the River Avon, but well worth it. After the event, I’m also told that the best view of Breamore Mill, the Avon valley and the chalk hills beyond, and the river snaking through lush, green meadows; is to be had from high up on Castle Hill, almost 2 kilometres to the south-east of the village.

I also noticed a concrete structure that seemed out of place and now know that is was one of many WW2 pillboxes built to guard the valley.

On to Minstead. We can always rely upon Tom to find us the most direct yet slowest route to anywhere. We are using Tom this week as we are driving Drew’s car, having returned our rental car in Southampton. Our rental car was a brand new Vauxhall Astra Turbo with sat nav. Our satnav was called Prudence. She was very British, and also had a love of roads so country they were unsealed and on one occasion stopped at a dead end 1 mile from where we wanted to be, but 7 miles away by road. But that’s another story.

We drove through parts of the forest on narrow unsealed roads, then across grassland and finally through forest again before reaching Minstead on the far eastern edge of TNF. It was 1.30 and time for lunch.

Our AA Guide Book had mentioned that “The Trusty Servant” Inn was the place to go. Over the front door hangs John Hoskins 1579 painting of “The Trusty Servant” and on a side wall outside is the allegorical verse”

A trusty servant's picture would you see,

This figure well survey, who'ever you be.

The porker's snout not nice in diet shows;

The padlock shut, no secret he'll disclose;

Patient, to angry lords the ass gives ear;

Swiftness on errand, the stag's feet declare;

Laden his left hand, apt to labour saith;

The coat his neatness; the open hand his faith;

Girt with his sword, his shield upon his arm,

Himself and master he'll protect from harm.

Both are synonymous with Winchester College, which isn’t that far away, and “The Trusty Servant” is still the name of the colleges new letter. This is the same college I wrote about in 2017. The college with a great game of “Rugby/Football” called Winkies. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winchester_College_football

It is claimed that the painting and verse are the first example of a "job description".

The food at this Inn was highly rated in 1974. It’s still highly rated. It’s pub food. Nothing extraordinary on the memu. Wild Boar and Apple Sausages with onion jam, roasted root vegetables and double fried chips. Sensational chips and Ches said her French Fries were brilliant as well. Ches had her usual Crabbies Ginger Beer and I decided on an Apple Cider. Dry and slightly bitter. Great.

Apart from pretty thatched cottages, there isn’t anything outstanding other than the most peculiar church. Apart from the tower, it doesn’t look like a church. As the guide book says, it looks like a row of cottages. There is an explanation.

I really do recommend that you follow this link for one of the best descriptions of a church I have come across. It’s all the more significant because this has to be one of the most idiosyncratic churches I have ever seen. Can I tempt you with this:

All Saints is a 13th century church refurbished in the 17th century. The brick tower was built in 1774, but the rest is basically a parish church that nobody could afford to rebuild and so the more notable local families merely paid for new extensions, or pews as they were known, to be attached to the church to house their families, their staff and their tenants. There are three such additions, north of the nave is the Minstead Lodge Pew with its own private entrance, and nearby, the luxurious Castle Malwood pew complete with a fireplace and upholstered seating, giving it the look of a rather comfortable drawing room. Most remarkable is the spacious Minstead Manor pew once furnished with a sofa and even a table and chairs where refreshments could be served by their staff.

https://dineanddivine.com/2017/10/22/minstead-all-saints-church/

We knew that the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was in the churchyard but didn’t have the detective nous to go in search of it. It appears that it is under a large tree in the churchyard. The only large tree we looked at had a hollow trunk with a rustic stick cross leaning inside it. It’s an ancient Yew tree that has one of its limbs propped up.

Because he was a believer in the spiritual world, they buried him at the back of the graveyard and the tree he was buried under was promptly struck by lightning. It appears that lightning struck twice because his wife had engraved “Faithful Husband” on his tombstone and had it removed when she discovered that he had had an affair.

Sir Arthur was originally buried in a vertical position in Crowborough and re-interred in Minstead by the family of his deceased first wife after the death of the second Lady Conan Doyle. I guess they wished they had left him where he was.

As I photographed the village, I noticed that the puddles were frozen and it was 3.30 pm. Enough was enough, home to a cold house … we had forgotten to put the heaters on.

I'll post reports on each of these locations, however this report could be quite short as we aren't getting out and about as much as we did for the previous 6 weeks.

One of our sons teaches music composition at Southampton University and we are staying with he and his partner until his 45th birthday and a concert performance of one of his works at the end of January. Then back home to Sydney hoping the high 30c temperatures are a thing of the past back there.

Drew says I sometimes “over think” things. Such as? Why were the water pools and ponds in The New Forest so intensely blue today?

It was cold today. Actually, it was freezing. As I posted on Facebook today:

“In Australia, we more often refer to temperatures as being in their low teens or high teens in winter. That's Centigrade degrees. Here in the UK, the gauge in Drew's car measures it in half degrees. Half a degree is import when it's still only 3c at 11.00 am and finally registers 3.5c shortly after. Then the internet advise that it may be 3.5c but feels like -1c.

When I see ice on the footpath at 3.30 pm, all I know is, IT"S FREEZING!

Despite the above, the sun was out .... not shining, but out. We enjoyed The New Forest today.”

As usual, I digress. The water was intensely blue. Apparently when light shines into water, the water molecules absorb certain colours depending on the depth of the water and the base (sandy or rocky). The colours not absorbed, mix to create the colour we see. OK, I’m over thinking. The water was intensively blue and probably accentuated by the green of the fields. Then again, not having seen the sun and a blue sky in 6 weeks probably might have something to do with it.

We decided to visit parts of The New Forest we missed in 2017. Rockbourne is actually just outside The New Forest in the far north west. It’s so close to Breamore (Bremmer), also on our list, that we decided to go there first and work our way back.

The New Forest isn’t all forest. Approx. a third is heath and grass, with a third of that, wet grassland. That’s where we drove slowly across The New Forest. Lots of wet grassland and horses and ponies. To repeat what I wrote last time, the land is largely unfenced and “common” land. The stock are owned but all just intermix and roam free.

Most of the horses weren’t feeding (the Donkeys were). They all appeared to be just standing beside any available shrub, eyes closed and soaking up the rays of the sun. On several occasions when they were standing in the road, they made no effort to move as we slowly drove around them.

It only took 30 minutes to drive from Southampton to Rockbourne. Even at 60kmph and through several small villages and some narrow country lanes. All easier to see when you are driving that much slower.

Rockbourne is one long street. Probably 600m. On the south side, many of the houses/cottages abut the road. On the north side, the road is flanked by a brook (that’s a stream or creek in Australia). Why call a brook a brook, when you can call it “Sweatfords Water”. Every house/cottage on that side is reached by its own little bridge. All of the houses on both side are either Tudor or Georgian and the majority thatched. It was a case of driving through the town exclaiming “OMG” from beginning to end. The end being the only parking available in the village. The “Rose and Thistle” pub was the only public parking available, so we parked there and doing the right thing, entered for a coffee/tea.

The manager was in the process of lighting the two fires. Real timber fires … there isn’t any shortage of plantation and fallen trees in TNF. Most places now have artificial coal fires (gas) and it was great to smell real timber burning. Wonderful atmosphere with hunting paraphernalia and turn of the century (19th) Vanity Fair paintings of cricketers and hunters, decorating the walls and ceiling of this old Tudor Inn.

Warmed a little, we worked our way down the village. With the sun in our eyes, I photographed every dwelling on the north side on the way down and both sides on the way back. For ¾ hour, we strolled. Said hello to two guys re-thatching a large cottage and dodged a constant stream of cars. Like Pitt/Burke Sts.

As we approached the “Rose and Thistle” on our return, Ches decided to visit the ladies inside, while I went around to the carpark … it was full. Ches returned to say that the hotel was packed. Bar and restaurant. So the cars we had dodged weren’t travelling through, but too. That explained a reserved sign on a table we had seen in the bar. On a Wednesday? No idea.

The other feature of Rockbourne is a Roman Villa. It is quite extensive, and largely consists of some mosaics, the foundations of 70 rooms, and one large rectangular foundation of the bathhouse, with the hypocaust exposed. It was closed for the winter and the hedge around it impenetrable. I only know what it looks like because I googled.

I should have googled before we went to Rockburne. All we had was our 1974 AA Touring Guide of GB which mentioned Tudor and Georgian cottages. For anyone reading this, who decides to also visit Rockbourne, here’s what we missed:

Thanks Wiki

Overview

Rockbourne is a village of thatched, brick and timber houses, next to a stream now known as Sweatfords Water. The village consists chiefly of one street almost half a mile long. The church is in the northeast of the main street. Close to the church, adjoining the north side of the churchyard, is a manorial complex consisting of small L-shaped 14th-century house, now used as part of a modern farmhouse; the remains of a large Elizabethan or Jacobean house a short distance to the east; a 13th-century chapel near its southeast angle; and a large 15th-century barn running northward from the chapel.

History

Rockbourne has a long history of human habitation. Three Neolithic long barrows are known within the parish boundaries, as well as the sites of over twenty Bronze Age bowl barrows. At Knoll Camp, there is also the site of an Iron Age Hill fort with a single bank and ditch. At West Park, Rockbourne Roman Villa has been excavated since the 1950s, revealing over 70 rooms, several with mosaic floors and hypocausts. The collection of finds from the site have been housed permanently in the museum building on the site, which is the only villa site in Hampshire open to the public.

The name Rockbourne, recorded as Rocheborne in 1086, may derive from Old English "Hrocaburna", Rooks' stream, or perhaps Rocky stream. In the earliest records Rockbourne was a royal manor. In the Domesday Book of 1086, Alwy son of Turber held a hide there which Wulfgeat had previously held of King Edward.[9] Saewin also held half a hide of the gift of King Edward, to which the sheriff in 1086 made an unsuccessful claim as part of the king's farm, but which at a later date reverted to the Crown.

Alwy was succeeded here as in Hale and Tytherley by the Cardenvilles, and in the 13th century William Cardenville held a free tenement in Rockbourne.[4] Before 1156 the manor had been granted to Baron Manser Bisset. He was succeeded before 1177 by a son Henry, and whose widow Iseuld was holding Rockbourne early in the next century. Their eldest son William died c. 1220, and was succeeded by his brother John, who died in 1241. Rockbourne passed to his daughter Ela, and then to her son John who assumed his mother's surname. He died in 1307, leaving a son John, who died unmarried in 1334, leaving the manor to his sister Margaret, at that time the wife of Robert Martin, on whom the manor was settled in 1338.[4]

Early in 1336 Robert Martin complained that a certain John de Crucheston (Crux Easton) and others had abducted Margaret his wife and taken away his goods. Not waiting for justice, he retaliated by breaking into the house of John de Crucheston and seizing his property. Some years later he took Crucheston prisoner, torturing him "with cords tied round his head and other torments, and extorting £1,150 from his friends for his release." Robert Martin died in 1355, his wife surviving him until 1373, when the manor passed to her eldest son by her first husband, Sir Walter de Romsey. It then passed by inheritance into the Keilway family, it being held by John Keilway on his death in 1547. His son Francis died in 1601–2, and his son Thomas succeeded to Rockbourne, which, already heavily mortgaged to Sir Anthony Ashley, he sold in 1608 to Sir Anthony's son-in-law, Sir John Cooper. Sir John Cooper was succeeded by his eldest son Anthony Ashley Cooper, created Earl of Shaftesbury in 1672, and the manor descended with the Earls of Shaftesbury.

The nearby manor of Rockstead, which Aldwin held before 1066, belonged to Hugh de Port in 1086. Rockstead had passed to Breamore Priory before 1291. It belonged to the priory at the Dissolution and was granted with its other possessions to Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter and Gertrude his wife in November 1536. Escheating to the Crown in 1539, it was granted to Anne of Cleves, but in 1548 passed to Sir Thomas Henneage and William Lord Willoughby, who in the following year sold it to William Keilway. After this date it followed the descent of Rockbourne and became merged in that manor, its name only surviving in Rockstead Farm.

On to Breamore pronounced “Bremmer”. Again according to our AA Guide, “pure Tudor’. Triangular in shape with the large houses along the base and a green with small cottages at the apex and a narrow street through to the main road.

Let’s get things straight. Yes, several lovely thatched houses along the base. A “green” that resembles more “wet grassland” than a green on which you might play cricket or have a picnic. It turns out it is “the Marsh (an important surviving manorial green)”

Again, while I quite liked what we saw and photographed, it might help if more info was available and a map wouldn’t go astray as some of the sites aren’t as close to the village as suggested.

The Saxon church and Breamore House are about three-quarters of a mile west of the road and we had no chance of finding them and we only stumbled on the River Avon because Tom (our satnav) took us over oit on our way across country to our final destination Minstead.

Before leaving Breamore however:

“History

Breamore Down has several Bronze Age bowl barrows. There is also a long barrow known as the Giant's Grave, originally 65m long and 26m wide with flanked ditches, it is now partly damaged. Breamore Down also has a mysterious mizmaze on its heights. Argument rages as to whether the Bronze Age people or mediaeval monks were responsible for these patterns cut in the turf.

The name Breamore, recorded as Brumore in 1086, may be derived from Old English "Brommor" meaning "broom(covered) marsh". At an early date the manor of Breamore belonged to the Crown, and in 1086 was part of the royal manor of Rockbourne. At an early date, probably by grant of Henry I, Breamore passed to the Earls of Devon, lords of the Isle of Wight, who held it from the king in chief. In 1299, Edward I assigned it to his consort, Margaret of France, but in 1302 Breamore was delivered to Hugh de Courtenay. From that time it descended with the Earls of Devon until it was granted, in 1467, to Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy. In 1475, Breamore escheated to the king, who granted it for life in 1490 to Sir Hugh Conway and Elizabeth his wife. In 1512, it was granted to Catherine of Yorkwidow of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon and her heirs. Her son Henry was created Marquess of Exeter in 1525, but was beheaded in 1538–9, when the manor again passed to the Crown.

The manor was granted in 1541 to the queen consort, Catherine Howard, and in 1544 to Catherine Parr, who, after the death of Henry VIII, married Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, to whom Breamore was granted by Edward VI in 1547. On his execution in 1549 it again passed to the Crown and was granted in 1579 by Elizabeth I to Christopher Hatton. William Dodington purchased from him and died in 1600 leaving a son and heir Sir William. From this date Breamore followed the descent of South Charford until 1741, when Francis Lord Brooke sold it to Samuel Dixon, preliminary to its sale to Sir Edward Hulse.

Breamore railway station opened in 1866. It was served by the Salisbury and Dorset Junction Railway, a line running north–south along the River Avon, connecting Salisbury to the North and Poole to the South. It closed in 1964, the disused station still exists on the road that leads east from the A338.

St Mary's church

The church of Saint Mary is an almost complete example of an Anglo-Saxon church. The building consists of a chancel and aisleless nave separated by square central tower. The east window with net like tracery dates from 1340. There is a "leper window" in the north wall. Seven "double-splayed" Saxon windows remain. The chancel arch and arch in west wall of the tower are 15th century. The tower houses four bells cast in late 16th and early 17th centuries. There is an Anglo Saxon inscription dating from reign of Ethelred II, and a badly mutilated Saxon rood with figures of Our Lady and Saint John.

Breamore Priory

Main article: Breamore Priory

The priory of Breamore was founded towards the end of the reign of Henry I by Baldwin de Redvers and Hugh his uncle, to whose descendants the advowson belonged. It was apparently visited by Richard II in 1384. Baldwin and Hugh de Redvers endowed their priory of Breamore with certain land in Breamore which formed the nucleus of the manor later known as Breamore Bulborn. Various donors added gifts of adjoining land which were merged in the manor.

On the dissolution of the priory in July 1536 the site was granted in November of that year with the manors of Breamore and Bulborn to Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter and his wife Gertrude. It then followed the descent of Breamore Bulborn, becoming merged in that manor.

Breamore House

Main article: Breamore House

Breamore House stands north-west of the church. The original house was a very fine late 16th-century building of brick and stone, but was unfortunately burnt in 1856. It was restored on the old lines, incorporating such of the old masonry as was left, and now from a short distance still resembles an Elizabethan building.[8]

Breamore stocks

The village stocks can be viewed by the A338 roadside. They were originally at the road junction, but are now opposite the Bat and Ball Hotel. They were restored after being badly damaged by a lorry. The stocks have a whipping post and horizontals with four leg holes. A modern roof has been erected over them.”

It’s not easy to stop near the old mill and bridge that span the River Avon, but well worth it. After the event, I’m also told that the best view of Breamore Mill, the Avon valley and the chalk hills beyond, and the river snaking through lush, green meadows; is to be had from high up on Castle Hill, almost 2 kilometres to the south-east of the village.

I also noticed a concrete structure that seemed out of place and now know that is was one of many WW2 pillboxes built to guard the valley.

On to Minstead. We can always rely upon Tom to find us the most direct yet slowest route to anywhere. We are using Tom this week as we are driving Drew’s car, having returned our rental car in Southampton. Our rental car was a brand new Vauxhall Astra Turbo with sat nav. Our satnav was called Prudence. She was very British, and also had a love of roads so country they were unsealed and on one occasion stopped at a dead end 1 mile from where we wanted to be, but 7 miles away by road. But that’s another story.

We drove through parts of the forest on narrow unsealed roads, then across grassland and finally through forest again before reaching Minstead on the far eastern edge of TNF. It was 1.30 and time for lunch.

Our AA Guide Book had mentioned that “The Trusty Servant” Inn was the place to go. Over the front door hangs John Hoskins 1579 painting of “The Trusty Servant” and on a side wall outside is the allegorical verse”

A trusty servant's picture would you see,

This figure well survey, who'ever you be.

The porker's snout not nice in diet shows;

The padlock shut, no secret he'll disclose;

Patient, to angry lords the ass gives ear;

Swiftness on errand, the stag's feet declare;

Laden his left hand, apt to labour saith;

The coat his neatness; the open hand his faith;

Girt with his sword, his shield upon his arm,

Himself and master he'll protect from harm.

Both are synonymous with Winchester College, which isn’t that far away, and “The Trusty Servant” is still the name of the colleges new letter. This is the same college I wrote about in 2017. The college with a great game of “Rugby/Football” called Winkies. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winchester_College_football

It is claimed that the painting and verse are the first example of a "job description".

The food at this Inn was highly rated in 1974. It’s still highly rated. It’s pub food. Nothing extraordinary on the memu. Wild Boar and Apple Sausages with onion jam, roasted root vegetables and double fried chips. Sensational chips and Ches said her French Fries were brilliant as well. Ches had her usual Crabbies Ginger Beer and I decided on an Apple Cider. Dry and slightly bitter. Great.

Apart from pretty thatched cottages, there isn’t anything outstanding other than the most peculiar church. Apart from the tower, it doesn’t look like a church. As the guide book says, it looks like a row of cottages. There is an explanation.

I really do recommend that you follow this link for one of the best descriptions of a church I have come across. It’s all the more significant because this has to be one of the most idiosyncratic churches I have ever seen. Can I tempt you with this:

All Saints is a 13th century church refurbished in the 17th century. The brick tower was built in 1774, but the rest is basically a parish church that nobody could afford to rebuild and so the more notable local families merely paid for new extensions, or pews as they were known, to be attached to the church to house their families, their staff and their tenants. There are three such additions, north of the nave is the Minstead Lodge Pew with its own private entrance, and nearby, the luxurious Castle Malwood pew complete with a fireplace and upholstered seating, giving it the look of a rather comfortable drawing room. Most remarkable is the spacious Minstead Manor pew once furnished with a sofa and even a table and chairs where refreshments could be served by their staff.

https://dineanddivine.com/2017/10/22/minstead-all-saints-church/

We knew that the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was in the churchyard but didn’t have the detective nous to go in search of it. It appears that it is under a large tree in the churchyard. The only large tree we looked at had a hollow trunk with a rustic stick cross leaning inside it. It’s an ancient Yew tree that has one of its limbs propped up.

Because he was a believer in the spiritual world, they buried him at the back of the graveyard and the tree he was buried under was promptly struck by lightning. It appears that lightning struck twice because his wife had engraved “Faithful Husband” on his tombstone and had it removed when she discovered that he had had an affair.

Sir Arthur was originally buried in a vertical position in Crowborough and re-interred in Minstead by the family of his deceased first wife after the death of the second Lady Conan Doyle. I guess they wished they had left him where he was.

As I photographed the village, I noticed that the puddles were frozen and it was 3.30 pm. Enough was enough, home to a cold house … we had forgotten to put the heaters on.