Eleanor

1000+ Posts

This trip report covers a week we spent in St Thegonnec in northern Brittany in September 2011. It was originally written for Slow Travel and Pauline has asked me to enter it on Slow Europe.

This was week three of the trip. Week 1 covering Southern Finistere is here. Week 2 covering Morbihan is here.

There is general information about Brittany here.

To St Thegonnec and Forges des Salles

It was another dull and damp start. We drove to ROHAN and now know why none of the guide books mention it. It is a small, unmemorable settlement on the Nantes Brest Canal. We then cut across country to GUELTAS, a small village around the church.

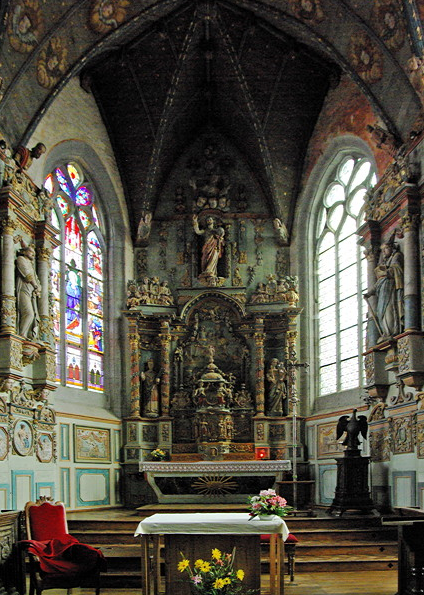

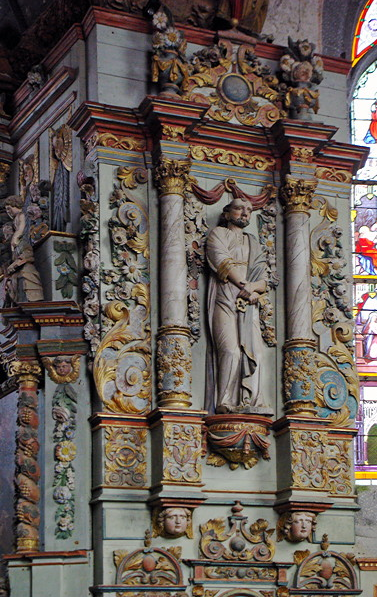

We had a personal guided tour of the church by the old soul who had let us in. She was having a marvellous time pointing out all the highlights of the church to us including photographs in the windows of two of the men from the village killed in WW1.

Next was MÛR-DE-BRETAGNE, a delightful small town with a lot of old houses and definitely not a village as described in the guide books, with shops, eateries and several old houses made of dark schist blocks. The church is C19th and has carvings of the 12 apostles in the porch.

We parked up in the drizzle for views of LAC DE GUERLÉDAN as we ate our lunch. Judging by the size of the car park this gets very busy in summer. We then continued along the north side of the Lake and up GORGES DE DAOULAS. This didn’t live up to the hype “most spectacular spot… river cuts through precipitous gorse clad rock formation…. slabs of rock rise vertically…” It was a pleasant wooded valley with a few bare rocky cliffs. It is probably better seen going down than up. We drove it both ways to check.

BON REPOSE ABBEY was busy with cars and people with bikes and walkers (which may have been linked in with the major mountain bike event that weekend). There are nice views of the river on the way to Salles de Forges and glimpses of the abbey through the trees.

FORGE DES SALLES is a small iron making hamlet in a steep river valley with deciduous woodland. It had been a major mining and iron making centre in the C18th. The buildings have been restored and are a fascinating place to visit.

We were the first to arrive after opening and had an individual guided tour with a young English lad who had moved to Brittany with his parents 5 years ago. He was informative and able to answer most of our increasingly detailed questions. It was a very worthwhile visit. For those who don’t want to have a guided tour there is an information leaflet numbering the different buildings around the site with information about them.

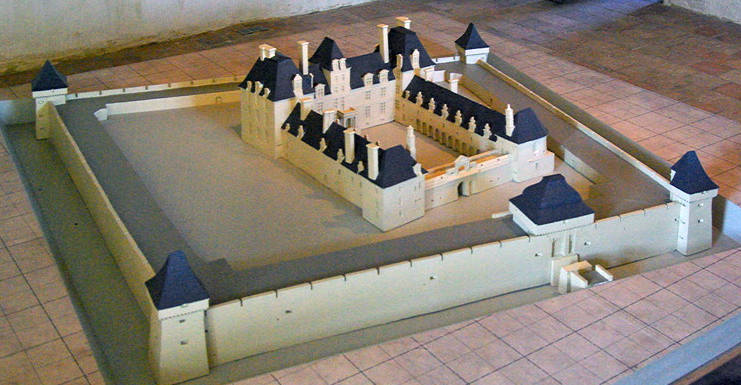

Mining was first established in the valley by the Rohan Family in 1623. The soil was rich in iron ore and there was plenty of wood for charcoal and an abundant supply of water. In 1802 the estate was bought by Compte de Janez who was very enlightened for the time and looked after the workers very well. His descendants still live in the big house. In the C18th this was one of the largest industrial sites in Brittany. Mining and processing of iron ore finished in 1880 and the buildings were gradually deserted. The site has now been restored as a museum.

The hamlet is dominated by the large house with its outbuildings, stables, kennels, carriage sheds as well as joinery and carpenter’s shop. The carpenter was responsible for maintenance of all roofing on the estate. This was originally where the Estate Manager and the Master of the Ironworks lived. Most of the building is C18th but the right wing was added in 1920 when the family moved in.

Beyond, the terraced garden rises up the side of the valley with a small orangery at the top (which now hides the water tower for the estate). This provided fruit, vegetables, flowers and herbs for the big house.

There was a terrace of single storey C18th iron workers cottages. One has been refurnished as it would have been in the 18thC. Others contain exhibitions about the site.

Each family lived in a single room with shale or beaten earth floor, fireplace and storage for hay above. At the back were two store rooms. Water came from a well but later water was provided to the cottages. Cooking was done over the fire but bread baked in the communal bread oven. A 6kg loaf would be baked as it kept better. Each family was allocated a plot of land to grow vegetables and keep animals. They had shared use of a horse which was stabled in the middle of the row of cottages. Families lived rent free. Life expectancy of the men was low. Widows were allowed to continue to live in the cottage and were given a pension. The son would take over the father’s job and live in the family home.

The row of two storey C19th cottages housed the foreman and office staff. Facing south, they caught all the sunlight. There was also a terrace of three storey manager’s houses, built when the Rohan family moved into the ‘big house'.

The Administration building is close to these and was also the pay office. The chief clerk was responsible for the book keeping of the estate which included forestry workers, charcoal burners, carters and miners living off the site as well as villagers. About 400 people were employed by the estate. Wages were paid every eight days. Miners and charcoal workers lived in the woods to be near their work. They would bring in ore or charcoal in horse drawn wagons which would be weighed and they would be given a chit to collect their pay from the office.

Behind the Administration building is the Chapelle St Eloi (St Eligius) who is the patron saint of metal workers.With no belfrey, it looks more lik a house than a church.

This has two entrances. the north entrance was used by the villagers and the main west entrance was reserved for the Master of the Ironworks, chief clerk and the family if in residence. They sat in larger and more comfortable seats at the back. The chapel is plain and simple as it was built by the Rohen family who were protestants. Now it is a catholic chapel.

At the far end of the village is the smithy with blacksmith’s cottage attached. Not only did the smith shoe horses he was also responsible for the repair of broken machinery. Nearby was a large canteen where the men were given a free midday meal and it served about 70 meals a day. Next to it was a was a small shop.

The men were paid in cash and the shop used money rather than a barter or truck system. This provided the women with all the essentials they could not provide themselves. It was also a meeting place to exchange gossip, especially when the packmen delivered goods.

There was communal bakery and cider press.

The French put a tax on grapes and cereals. There was no tax on apples or buckwheat which is one of the reasons Brittany produced cider rather than wine and used buckwheat (in crepes) rather than wheat based products. The cider press could produce 800l of cider in a pressing. The men were given an allowance and would drink cider in the canteen.

The Compte de Janez family provided a small free school for the children. This was well away from the industrial site to ‘spare the children noise and fumes’. About 50 children attended the school. It was run by the Sisters of the Holy Spirit from St Brieuc, who also acted as nurses to the community. French rather than Breton was used in the school. Very intelligent children were identified and the Compte would pay for their further education. At the end of primary school the boys became apprentices. The girls stayed with their mothers and learnt housekeeping skills. The school stayed open until 1970. The Compte’s children attended the school before going to boarding school. As the school building no longer exists, a building in the village has been converted into a schoolroom to show what an C18th school was like.

The blast furnaces, charcoal and iron store are in the centre of the village and horses pulled wagons on tramlines.

Originally there were three furnaces in the valley, each with a lake to provide power for the waterwheel working the bellows. They ran for nine months each year as there was not enough water to run them during the summer. This time was used to repair/refurbish the furnaces. Gradually two fell out of use leaving the main furnace in the village.

Originally all produce came in or out by horse and cart but once the Nantes Brest Canal was constructed output increased rapidly. There were large storage sheds for iron ore.

The charcoal store was large and open to the outside, to reduce the risk of explosion.

There was a lime kiln to produce lime from locally mined limestone.

Iron ore, charcoal and lime were taken by horse drawn wagons from the stores along tramways and tipped into the top of the furnace.

The waterwheel worked two huge bellows pumping hot air into the base of the furnace. They got more money for finished product although some wrought iron was sold to nail makers in Brittany. Artisans used the wrought iron to produce agricultural machinery. During the Napoleonic Wars they made link chained cannon balls. The slag was used for roads or building work.

Iron working closed down around 1880 as furnaces nearer the coast could produce more iron. The Furnace was demolished in 1887. A new furnace has been rebuilt on the site and contains some of the iron working tools. The pond was filled in as a health hazard.

This was a fascinating visit, brought to life by a guide who was passionate about the site. For any one interested in industrial archaeology, it is a must.

It was then a fast drive to St Thegonnec. By now the sun had come out and it was a glorious run over the top of the Monts d’ Arrée. These are heather moorlands with rocky outcrops with good views across the plain north.

Beyond was gentle rolling countryside with a lot of woodland and fields of maize and pasture.

This was week three of the trip. Week 1 covering Southern Finistere is here. Week 2 covering Morbihan is here.

There is general information about Brittany here.

To St Thegonnec and Forges des Salles

It was another dull and damp start. We drove to ROHAN and now know why none of the guide books mention it. It is a small, unmemorable settlement on the Nantes Brest Canal. We then cut across country to GUELTAS, a small village around the church.

We had a personal guided tour of the church by the old soul who had let us in. She was having a marvellous time pointing out all the highlights of the church to us including photographs in the windows of two of the men from the village killed in WW1.

Next was MÛR-DE-BRETAGNE, a delightful small town with a lot of old houses and definitely not a village as described in the guide books, with shops, eateries and several old houses made of dark schist blocks. The church is C19th and has carvings of the 12 apostles in the porch.

We parked up in the drizzle for views of LAC DE GUERLÉDAN as we ate our lunch. Judging by the size of the car park this gets very busy in summer. We then continued along the north side of the Lake and up GORGES DE DAOULAS. This didn’t live up to the hype “most spectacular spot… river cuts through precipitous gorse clad rock formation…. slabs of rock rise vertically…” It was a pleasant wooded valley with a few bare rocky cliffs. It is probably better seen going down than up. We drove it both ways to check.

BON REPOSE ABBEY was busy with cars and people with bikes and walkers (which may have been linked in with the major mountain bike event that weekend). There are nice views of the river on the way to Salles de Forges and glimpses of the abbey through the trees.

FORGE DES SALLES is a small iron making hamlet in a steep river valley with deciduous woodland. It had been a major mining and iron making centre in the C18th. The buildings have been restored and are a fascinating place to visit.

We were the first to arrive after opening and had an individual guided tour with a young English lad who had moved to Brittany with his parents 5 years ago. He was informative and able to answer most of our increasingly detailed questions. It was a very worthwhile visit. For those who don’t want to have a guided tour there is an information leaflet numbering the different buildings around the site with information about them.

Mining was first established in the valley by the Rohan Family in 1623. The soil was rich in iron ore and there was plenty of wood for charcoal and an abundant supply of water. In 1802 the estate was bought by Compte de Janez who was very enlightened for the time and looked after the workers very well. His descendants still live in the big house. In the C18th this was one of the largest industrial sites in Brittany. Mining and processing of iron ore finished in 1880 and the buildings were gradually deserted. The site has now been restored as a museum.

The hamlet is dominated by the large house with its outbuildings, stables, kennels, carriage sheds as well as joinery and carpenter’s shop. The carpenter was responsible for maintenance of all roofing on the estate. This was originally where the Estate Manager and the Master of the Ironworks lived. Most of the building is C18th but the right wing was added in 1920 when the family moved in.

Beyond, the terraced garden rises up the side of the valley with a small orangery at the top (which now hides the water tower for the estate). This provided fruit, vegetables, flowers and herbs for the big house.

There was a terrace of single storey C18th iron workers cottages. One has been refurnished as it would have been in the 18thC. Others contain exhibitions about the site.

Each family lived in a single room with shale or beaten earth floor, fireplace and storage for hay above. At the back were two store rooms. Water came from a well but later water was provided to the cottages. Cooking was done over the fire but bread baked in the communal bread oven. A 6kg loaf would be baked as it kept better. Each family was allocated a plot of land to grow vegetables and keep animals. They had shared use of a horse which was stabled in the middle of the row of cottages. Families lived rent free. Life expectancy of the men was low. Widows were allowed to continue to live in the cottage and were given a pension. The son would take over the father’s job and live in the family home.

The row of two storey C19th cottages housed the foreman and office staff. Facing south, they caught all the sunlight. There was also a terrace of three storey manager’s houses, built when the Rohan family moved into the ‘big house'.

The Administration building is close to these and was also the pay office. The chief clerk was responsible for the book keeping of the estate which included forestry workers, charcoal burners, carters and miners living off the site as well as villagers. About 400 people were employed by the estate. Wages were paid every eight days. Miners and charcoal workers lived in the woods to be near their work. They would bring in ore or charcoal in horse drawn wagons which would be weighed and they would be given a chit to collect their pay from the office.

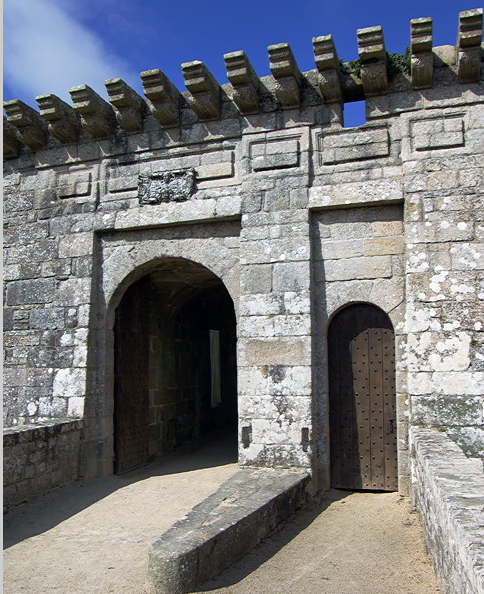

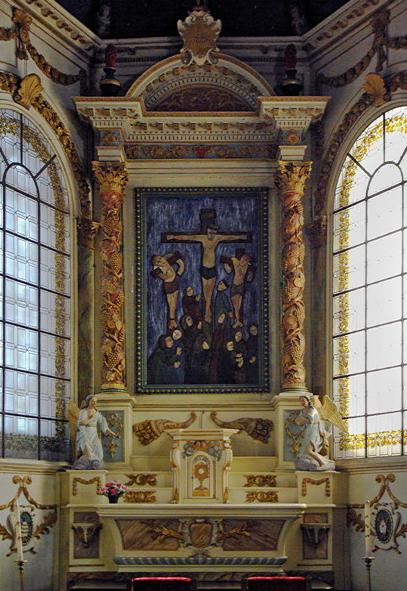

Behind the Administration building is the Chapelle St Eloi (St Eligius) who is the patron saint of metal workers.With no belfrey, it looks more lik a house than a church.

This has two entrances. the north entrance was used by the villagers and the main west entrance was reserved for the Master of the Ironworks, chief clerk and the family if in residence. They sat in larger and more comfortable seats at the back. The chapel is plain and simple as it was built by the Rohen family who were protestants. Now it is a catholic chapel.

At the far end of the village is the smithy with blacksmith’s cottage attached. Not only did the smith shoe horses he was also responsible for the repair of broken machinery. Nearby was a large canteen where the men were given a free midday meal and it served about 70 meals a day. Next to it was a was a small shop.

The men were paid in cash and the shop used money rather than a barter or truck system. This provided the women with all the essentials they could not provide themselves. It was also a meeting place to exchange gossip, especially when the packmen delivered goods.

There was communal bakery and cider press.

The French put a tax on grapes and cereals. There was no tax on apples or buckwheat which is one of the reasons Brittany produced cider rather than wine and used buckwheat (in crepes) rather than wheat based products. The cider press could produce 800l of cider in a pressing. The men were given an allowance and would drink cider in the canteen.

The Compte de Janez family provided a small free school for the children. This was well away from the industrial site to ‘spare the children noise and fumes’. About 50 children attended the school. It was run by the Sisters of the Holy Spirit from St Brieuc, who also acted as nurses to the community. French rather than Breton was used in the school. Very intelligent children were identified and the Compte would pay for their further education. At the end of primary school the boys became apprentices. The girls stayed with their mothers and learnt housekeeping skills. The school stayed open until 1970. The Compte’s children attended the school before going to boarding school. As the school building no longer exists, a building in the village has been converted into a schoolroom to show what an C18th school was like.

The blast furnaces, charcoal and iron store are in the centre of the village and horses pulled wagons on tramlines.

Originally there were three furnaces in the valley, each with a lake to provide power for the waterwheel working the bellows. They ran for nine months each year as there was not enough water to run them during the summer. This time was used to repair/refurbish the furnaces. Gradually two fell out of use leaving the main furnace in the village.

Originally all produce came in or out by horse and cart but once the Nantes Brest Canal was constructed output increased rapidly. There were large storage sheds for iron ore.

The charcoal store was large and open to the outside, to reduce the risk of explosion.

There was a lime kiln to produce lime from locally mined limestone.

Iron ore, charcoal and lime were taken by horse drawn wagons from the stores along tramways and tipped into the top of the furnace.

The waterwheel worked two huge bellows pumping hot air into the base of the furnace. They got more money for finished product although some wrought iron was sold to nail makers in Brittany. Artisans used the wrought iron to produce agricultural machinery. During the Napoleonic Wars they made link chained cannon balls. The slag was used for roads or building work.

Iron working closed down around 1880 as furnaces nearer the coast could produce more iron. The Furnace was demolished in 1887. A new furnace has been rebuilt on the site and contains some of the iron working tools. The pond was filled in as a health hazard.

This was a fascinating visit, brought to life by a guide who was passionate about the site. For any one interested in industrial archaeology, it is a must.

It was then a fast drive to St Thegonnec. By now the sun had come out and it was a glorious run over the top of the Monts d’ Arrée. These are heather moorlands with rocky outcrops with good views across the plain north.

Beyond was gentle rolling countryside with a lot of woodland and fields of maize and pasture.

Last edited: